All too often, academic writing is tone deaf to the music of language. Just as we tend to consider unprofessional any writing that is playful, engaging, funny, or moving, so too with writing that is musical. A professional monotone is the scholar’s voice of choice. This stance leads to two big problems. One is that it puts off the reader, exactly the person we should be trying to draw into our story. Why so easily abandon one of the great tools of effective rhetoric? Another is that it alienates academic writers from their own words, forcing them to adopt the generic voice of the pedant rather than the particular voice the person who is the author.

For better or for worse — usually for worse — we as scholars are contributing to the literary legacy of our culture, so why not do so in a way that sometimes sings or at least doesn’t end on a false note. Speaking of which, consider a quote from one of the masters of English prose, Abraham Lincoln, from the last paragraph of his first inaugural address. Picture him talking at the brink of the nation’s most terrible war, and then listen to his melodic phrasing:

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

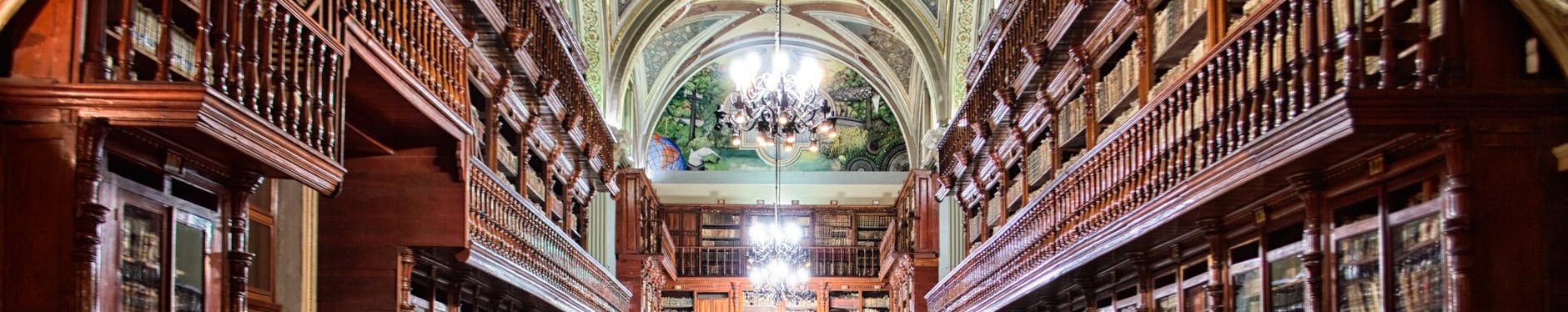

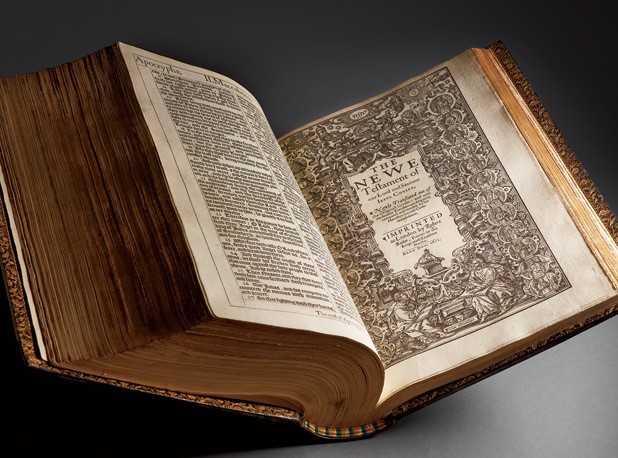

In the English language, there are two rhetorical storehouses that for centuries have grounded writers like Lincoln — Shakespeare and the King James Bible. Both are compulsively quotable, and both provide models for how to combine meaning and music in the way we write.

Take a look at this lovely piece by Ann Wroe, an appreciation of the music of the King James Bible, which makes all the other translations sound tone deaf.

Published in the Economist

March 30, 2011

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE SOUND

Ann Wroe

The King James Bible is 400 years old this year, and the music of its sentences is still ringing out. But what exactly made it so good? Ann Wroe gives chapter and verse…

Like many Catholics, I came late to the King James Bible. I was schooled in the flat Knox version, and knew the beautiful, musical Latin Vulgate well before I was introduced to biblical beauty in my own tongue. I was around 20, sitting in St John’s College Chapel in Oxford in the glow of late winter candlelight, though that fond memory may be embellished a little. A reading from the King James was given at Evensong. The effect was extraordinary: as if I had suddenly found, in the house of language I had loved and explored all my life, a hidden central chamber whose pillars and vaulting, rhythm and strength had given shape to everything around them.

The King James now breathes venerability. Even online it calls up crammed, black, indented fonts, thick rag paper and rubbed leather bindings—with, inside the heavy cover, spidery lists of family ancestors begotten long ago. To read it is to enter a sort of communion with everyone who has read or listened to it before, a crowd of ghosts: Puritan women in wide white collars, stern Victorian fathers clasping their canes, soldiers muddy from killing fields, serving girls in Sunday best, and every schoolboy whose inky fingers have burrowed to 2 Kings 27, where Rabshakeh says, “Hath my master not sent me to the men which sit on the wall, that they may eat their own dung, and drink their own piss with you?”

When it appeared, moreover, it was already familiar, in the sense that it borrowed freely from William Tyndale’s great translation of a century before. Deliberately, and with commendable modesty, the members of King James’s translation committees said they did not seek “to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one, but to make a good one better”. What exactly they borrowed and where they improved is a detective job for scholars, not for this piece. So where it mentions “translators” Tyndale is included among them, the original and probably the best; for this book still breathes him, as much as them.

In both his time and theirs this was a modern translation, the living language of streets, docks, workshops, fields. Ancient Israel and Jacobean England went easily together. The original writers of the books of the Old Testament knew about pruning trees, putting on armour, drawing water, the readying of horses for battle and the laying of stones for a wall; and in the King James all these activities are still evidently familiar, the jargon easy, and the language light. “Yet man is born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward”, runs the wonderful phrase in Job 5: 7, and we are at a blacksmith’s door in an English village, watching hammer strike anvil, or kicking a rolling log on our own cottage hearth. “Hard as a piece of the nether millstone” brings the creak of a 17th-century mill, as well as the sweat of more ancient hands. In both worlds, “seedtime and harvest” are real seasons. This age-old continuity comforts us, even though we no longer know or share it.

By the same token, the reader of the King James lives vicariously in a world of solid certainties. There is nothing quaint here about a candle or a flagon, or money in a tied leather purse; nothing arcane about threads woven on a handloom, mire in the streets or the snuffle of swine outside the town gates. This is life. Everything is closely observed, tactile, and has weight. When Adam and Eve sew fig-leaves together to cover their shame they make “aprons” (Genesis 3: 7), leather-thick and workmanlike, the sort a cobbler might wear. Even the colours invoked in the King James—crimson, scarlet, purple—are nouns rather than adjectives (“though your sins be as scarlet”, Isaiah 1: 18), sold by the block as solid powder or heaped glossy on a brush. And God’s intervention in this world, whether as artist, builder, woodsman or demolition man, is as physical and real as the materials he works with.

English, of course, was richer in those days, full of neesings and axletrees, habergeons and gazingstocks, if indeed a gazingstock has a plural. Modern skin has spots: the King James gives us botches, collops and blains, horridly and lumpily different. It gives us curious clutter, too, a whole storehouse of tools and knick-knacks whose use is now half-forgotten—nuff-dishes, besoms, latchets and gins, and fashions seemingly more suited to a souped-up motor than to the daughters of Jerusalem:

The chains, and the bracelets, and the mufflers,

The bonnets, and the ornaments of the legs, and the

headbands, and the tablets, and the earrings,

The rings, and nose jewels,

The changeable suits of apparel, and the mantles, and the

wimples, and the crisping pins… (Isaiah 3: 19-22)

“Crisping pins” have now been swallowed up (in the Good News version) in “fine robes, gowns, cloaks and purses”. And so we have lost that sharp, momentary image of varnished nails pushing pins into unruly frizzes of hair, and lipsticked mouths pursed in concentration, as the daughters of Zion prepare to take on the town. These women are “froward”, a word that has been lost now, but which haunts the King James like a strutting shadow with a shrill, hectoring voice. Few lines are longer-drawn out, freighted with sighs, than these from Proverbs 27:15: “A continual dropping in a very rainy day and a contentious woman are alike.”

Other characters cause trouble, too. In the King James, people are aggressively physical. They shoot out their lips, stretch forth their necks and wink with their eyes; they open their mouths wide and say “Aha, aha”, wagging their heads, in ways that would get them arrested in Wal-Mart. They do not simply refuse to listen, but pull away their shoulders and stop their ears; they do not merely trip, but dash their feet against stones. Sex is peremptory: men “know” women, lie with them, “go in unto” them, as brisk as the women are available. “Begat” is perhaps the word the King James is best known for, list after list of begetting. The curt efficiency of the word (did no one suggest “fathered”?) makes the erotic languor of the Song of Solomon, with its lilies and heaps of wheat, shine out like a jewel.

The world in which these things happen has a particular look and feel that comes not just from the original authors, but often from the translators and the words they favoured. Mystery colours much of it. They like “lurking places of the villages” (Psalms 10: 8), “secret places of the stairs” (Song of Solomon 2:14), and things done “privily”, or “close”. God hides in “pavilions” that seem as mysterious as the shifting dunes of the desert, or the white flapping tents of the clouds. The word “creeping” is used everywhere to suggest that something lives; very little moves fast here, and heads and bellies are bent close to the earth. Even flying is slow, through the thick darkness. People go forth abroad, and waters come down from above, with considerable effort, as though through slowly opening layers. Elements are divided into their constituent parts: the waters of the sea, a flame of fire. A rainbow curves brightly away from the astonished, struggling observer, “in sight like unto an emerald” (Revelation 4: 3). But the grandeur of the language gives momentousness even to the corner of a room, a drain running beside a field, a patch of abandoned ground:

I went by the field of the slothful, and by the vineyard of the

man void of understanding;

And lo, it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had

covered the face thereof, and the stone wall thereof was

broken down.

Then I saw, and considered it well; I looked upon it, and

received instruction.

Yet a little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands

to sleep… (Proverbs 24: 30-33)

In such places shepherds “abide” with their sheep, motionless as figures made of stone. This landscape is carved broad and deep, like a woodcut, with sharply folded mountains, thick woven water, stylised trees and cities piled and blocked as with children’s bricks (all the better to be scattered by God later, no stone upon another). A sense of desolation haunts these streets and gates, echoing and shelterless places in which even Wisdom runs wild and cries. Yet within them sometimes we find a scene paced as tensely as in any modern novel, as when a young man in Proverbs steps out,

Passing through the street near her corner; and he went the

way to her house,

In the twilight, in the evening, in the black and dark night:

And, behold, there met him a woman with the attire of an

harlot, and subtil of heart. (Proverbs 7: 8-10)

Just as stained glass shines more brightly for being set in stone, so the King James gains in splendour by comparison with the Revised Standard, Good News, New International and Heaven-knows-what versions that have come later. Thus John’s magnificent “The Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1: 1), has become “The Word was already existing”, scholarship usurping splendour. That lilting line in Genesis (1: 8), “And the evening and the morning were the second day” (note that second “the”, so apparently expendable, yet so necessary to the music) becomes “There was morning, and there was evening”, a broken-backed crawl. The fig-leaf aprons are now reduced to “coverings for themselves”. And the garden planted “eastward in Eden” (Genesis 2: 8), another of the King James’s myriad and scarcely conscious touches of grace, has become “to the east, in Eden” a place from which the magic has drained away.

Everywhere modern translations are more specific, doubtless more accurate, but always less melodious. The King James, deeply scholarly as it is, displaying the best learning of the day, never forgets that the word of God must be heard, understood and retained by the simple. For them—children repeating after the teacher, workers fidgeting in their best clothes, Tyndale’s own whistling ploughboy—rhythm and music are the best aids to remembering. This is language not for silent study but for reading and declaiming aloud. It needs to work like poetry, and poetry it is.

The King James is famous for its monosyllables, great drumbeats of description or admonition: “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light” (Genesis 1: 3); “The fool hath said in his heart, There is no God” (Psalms 14: 1); “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread” (Genesis 3: 19). These are fundaments, bases, bricks to build with. Yet its rhythms are also far cleverer than that, endlessly and subtly adjusted. Typically, a King James sentence has two parts broken by a pause around the mid-point, with the first part slightly more declaratory and the second slightly more explanatory: the stronger syllables massed towards the beginning, the weaker crowding softly towards their end. “Surely there is a vein for the silver, and a place for gold where they fine it” (Job 28: 1); “He buildeth his house as a moth, and as a booth that the keeper maketh” (Job 27: 18). But sometimes the order is inverted, and the words too: “As the bird by wandering, as the swallow by flying, so the curse causeless shall not come” (Proverbs 26: 2); “Out of the south cometh the whirlwind: and cold out of the north” (Job 37: 9). Perhaps the whirlwind itself has disordered things. This contrapuntal system even allows for a bit of bathos and fun: “Divers weights are an abomination unto the lord; and a false balance is not good” (Proverbs 20: 23).

Certain devices were available then which modern writers may well envy. The old English language allowed rhythms and syncopations that cannot be employed any more. Consider the use of “even”, dropped in with an almost casual flourish: “And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind” (Revelations 6: 13). Or “neither”, used in the same way: “Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it” (Song of Solomon 8: 7). Modern translations separate those two thoughts, but the beauty lies in their conjunction with a word as light as air.

Undoubtedly the King James has been enhanced for us by the music that now curls round it. “For unto us a child is born” (Isaiah 9: 6) can’t now be read without Handel’s tripping chorus, or “Man that is born of a woman” without Purcell’s yearning melancholy (“He cometh forth like a flower, and is cut down” Job 14: 2). Even “To every thing there is a season”, from Ecclesiastes (3: 1), is now overlaid with the nasal, gently stoned tones of Simon & Garfunkel. Yet the King James also lured these musicians in the beginning, snaring them with stray lines that were already singing. “Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples, for I am sick of love” (Song of Solomon 2: 5). “Thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns” (Psalms 22: 21). “The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork” (Psalms 19: 1). “I am a brother to dragons, and a companion to owls” (Job 30: 29). Or this, also from the Book of Job, possibly the most beautiful of all the Bible’s books—a passage that flows from one astonishingly random and sudden question, “Hast thou entered into the treasures of the snow?” (Job 38:22):

Hath the rain a father? Or who hath begotten the drops of

dew?

Out of whose womb came the ice? And the hoary frost of

heaven, who hath gendered it?

The waters are hid as with a stone, and the face of the deep

is frozen.

Canst thou bind the sweet influences of Plaeiades, or loose

the bands of Orion? (Job 38:28-31)

The beauty of this is inherent, deep in the original mind and eye that formed it. But again, the translators have made choices here: “hid” rather than “hidden”, “gendered” rather than “engendered”, all for the very best rhythmic reasons. We can trust them; we know that they would certainly have employed “hidden” and “engendered” if the music called for it. Unfailingly, their ear is sure. And if we suspect that rhythm sometimes matters more than meaning, that is fine too: it leaves space for the sacred and numinous, that which cannot be grasped, that which lies beyond all words, to move within the lines.

That subtle notion of divinity, however, is seldom uppermost in the Old Testament. This God smites a lot. Three close-printed columns of Young’s Concordance are filled with his smiting, lightly interspersed with other people’s. Mere men use hand weapons, bows and arrows, or, with Jacobean niftiness, “the edge of the sword”; but the God of the King James simply smites, whether Moabites or Jebusites, vines or rocks or first-born, like a broad, bright thunderbolt. No other word could be so satisfactory, the opening consonants clenched like a fist that propels God’s anger down, and in, and on. We know that these are tough workman’s hands: this is the God who “stretcheth out the north over the empty place, and hangeth the earth upon nothing” (Job 26: 7). Smiting must have survived after the King James; but perhaps it was now so soft with over-use, so bruised, that it faded out of the language.

This God surprises, too. He “hisses unto” people, perhaps a cross between a whistle and a whoop, as if marshalling a yard of hens. God goes before, “preventing” us; he whips off our disguises, our clothes or our leaves, “discovering” us, and the shock of the original meanings of those words alerts us to the origins of power itself. “Who can stay the bottles of heaven?” cries a voice in Job 38: 37; and we suspect God again, like a teenage yob this time, lurking in his pavilion of cloud.

At moments like this it also seems that the translators themselves might be mystified, fingers scratching neat beards while they survey the incomprehensible words. Did they really understand, for example, that odd medical diagnosis in Proverbs: “The blueness of a wound cleanseth away evil; so do stripes the inward parts of the belly” (20: 30)? Or these lines from the last chapter of Ecclesiastes, the mystifying staple of so many funerals?

…they shall be afraid of that which is high, and fears shall

be in the way, and the almond tree shall flourish, and

the grasshopper shall be a burden, and desire shall fail;

because man goeth to his long home, and the mourners

go about the streets:

Or ever the silver cord be loosed, or the golden bowl be

broken, or the pitcher be broken at the fountain, or the

wheel broken at the cistern.

Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was… (Ecclesiastes 12: 5-7)

These are surreal images, unlikely litter in the fields and streets; but they are made all the more potent by the heavy phrasing, the inevitability of the building lines, and the conscious repetition, broken, broken, broken. We know our translators have plenty of synonyms up their sleeves. They choose not to use them. When these lines are read, though we barely know what they mean, they spell despair. And they are meant to, as the man in the pulpit in a moment reminds us:

Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity (Ecclesiastes 12: 8)

Yet often, too, a spirit of playfulness seems to be at work. Consider, lastly, the rain. This is ordinary rain most of the time, malqosh in the Hebrew, and all modern translations make it so. But in the King James we also have “the latter rain”, and “small rain”, and we are alerted to their delicacy and difference. Small rain (“as the small rain upon the tender herb” Deuteronomy 32: 2) is presumably the sort that blows in the air, that makes no imprint on a puddle; the Irish would call it a soft day. And latter rain, perhaps, is the sort that skulks at the end of an afternoon, or suddenly cascades down in an autumn gust, or patters for a desultory few minutes after a day of approaching thunder—and then we open our mouths wide to it, laughing, grateful, as for the word of God.

Ann Wroe [3] is obituaries and briefings editor of The Economist and author of “Being Shelley”