This post is a piece I originally published in a 2000 book honoring David Tyack, Reconstructing the Good in Education: Coping with Intractable American Dilemmas. which was edited by Larry Cuban and Dorothy Shipps. Here’s a link to a PDF of the chapter.

Two years ago I did a short post about Albert Hirschman’s book, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, in which I drew out a few key implications of his analysis for a richer understanding of the problems with public education. The difficulty with education is that if people are unhappy with the quality of schooling, they can always fix the issue by leaving this school and sending children to a different school — the option that Hirschman calls “exit.” As a political institution, however, schools are not responsive to the exit of dissatisfied customers. Instead, they respond when people stay and fight for change — the option that Hirschman calls “voice.” Here I explore these implications in more depth, arguing that you can exit education as a private good but you can’t exit education as a public good.

In this essay, I explore the political economy of public schooling in an effort to understand the conflict between public and private goals that has shaped this institution and to identify alternative strategies for dealing with this conflict. I draw initial insights from Albert Hirschman’s classic book, “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.” According to Hirschman, organizations that become dysfunctional – unable to satisfy the needs of their members or customers – provoke two kinds of responses that offer hope of restoring the organization to a greater level of effectiveness. One is economic, in which customers exit from the organization by choosing to buy the product of another more effective firm; the offending firm either quickly gets the message and makes the necessary adjustments to bring back its customers or it goes out of business. The other is political, in which members choose not to exit but to stay and exercise their voice within the organization in a effort to provoke the reforms they deem necessary.

The problem for public schooling is that it occupies a position between these alternatives. As a publicly constituted, funded, and governed institution, it is primarily sensitive to voice in resolving its problems; but its organizational failures are most likely to provoke unhappy customers to exit. The most dissatisfied (and politically influential) customers choose to send their children to private schools (or suburban public schools), leaving public schools (especially in large cities) with their funding intact and with little incentive to change. For proponents of school choice, charters, and vouchers, the solution is simple: Shift them entirely into the economic realm by removing guaranteed public funding, thus making them vulnerable to the possibility that funding will exit along with unhappy consumers. For those who oppose this move to privatize public schooling because they see public schools as a truly common ground within the community, the solution is equally simple: Shift schools entirely into the political realm by removing the possibility for an easy exit and forcing people to stay and fight for improvement from within.

The problem with the economic solution is that it is radically anti-social. By making education entirely subject to the demands of the individual consumer, it leaves no one looking out for the public interest in public education. And the problem with the political solution is that it is radically illiberal. By making education a public monopoly, it leaves no opportunity for individuals to make meaningful educational choices.

A viable way out of this dilemma is to recognize that excluding the exit option is unnecessary, since there is really no way for a citizen to escape from being a consumer of public education. As citizens, taxpayers, employers, and workers, people who send their children to private schools must still live with the consequences of public education, as it succeeds or fails to provide the political competence and human capital without which the society cannot function. From this perspective, then, the way to convince people to stay and voice their concerns with the failings of public education (rather than to exit and turn their backs on these failings) is to demonstrate to them that they have an irreducible stake in the success of this institution. Since exit is functionally impossible, voice becomes the logical option, with the result that loyalty to the public schools becomes the rational choice for all citizens, whether or not they have children enrolled in these schools.

No Exit:

Public Education as an Inescapably Public Good

David F. Labaree

Urban schools did not create the injustices of American urban life, although they had a systematic part in perpetuating them. It is an old and idle hope to believe that better education alone can remedy them. Yet in the old goal of a common school, reinterpreted in radically reformed institutions, lies a legacy essential to a quest for social justice. (Tyack 1974: 12)

Here in the closing paragraph of his prologue to The One Best System, David Tyack spelled out the basic elements of the philosophy that has guided his writing about American education from his earliest days as a scholar to the present. He acknowledges that public education has long helped perpetuate social inequality in the United States but refuses to blame it for the existence of this inequality. And he argues that public education has within it the potential to support the quest for social justice, without giving in to the temptation to assign education the role of savior. As a result, the story he tells about the history of American education is not filled with saints and sinners, but it nonetheless revolves around a set of principles about what constitutes a good society and a good school. The common school ideal, though never fully realized, still captures for him qualities that are woven deeply into American life and that continue to offer possibilities for a better life. This is not a romantic conception of school and society, but neither is it a vision filled with despair, for the common school represents something basic about who we are as a people and what kind of society we can become.

Over the years, he has defended this vision of public education from the canonizing efforts of many historical triumphalists and from the demonizing efforts of many historical revisionists. As he put it several pages earlier in the same prologue, “I endorse neither the euphoric glorification of public education as represented in the traditional historiography nor the current fashion of berating public school people and regarding the common school as a failure” (1974: 9). This principled position in the middle ground of the debate about public schools is particularly important at the close of the twentieth century, when the rightward drift in American political culture has put all public institutions on the defensive. In an era when markets are triumphant and governments are in retreat, we find that the favored solution to every public problem is to privatize it. Have government get out of the way, we are told, and let markets work things out through the magic of competition (for providers) and choice (for consumers). Words like “common” or “public” for defining school have become epithets connoting drab standardization and relentless mediocrity: public school as public housing project, providing marginal education for the unfortunate and (perhaps) undeserving.

Under such conditions, the temptation is to counter the thunder for all things private with an equal thunder for all things public, to defend the public schools as they are against all comers. To one degree or another, a number of scholars have yielded to this temptation in recent years.[i] In this politically charged setting, Tyack’s effort to combine strong support for the principles of public education with sharp criticism for particular practices within this institution presents us with an especially timely and helpful model to follow.

In keeping with the spirit of Tyack’s work, my aim in this essay is to examine the way that implementation of the common school ideal has led to particular forms of educational failure while at the same time examining the negative educational consequences of the alternative put forward by market-oriented reformers, who propose to abandon of the common school ideal altogether on the grounds that it is unworkable and counterproductive. This analysis leads me to explore the political economy of public schooling in the U.S. in an effort to understand the conflict between public and private goals for this institution, to consider the consequences that each goal has had on it, for good and ill, and to consider strategies that offer possibilities for dealing with its problems while preserving its essential publicness.

The core of the American conflict over education is the question of whether public education should be seen primarily as a public good or a private good. In the American setting, where markets have long held pride of place and government has long been viewed with suspicion, the sense of education as a private good historically has been a powerful force. This orientation has become especially pronounced in the last several decades, when private solutions have been sweeping the field and the public sector has been in ideological and programmatic retreat. Putting ideology to the side for the moment, it is important to examine the practical consequences for schools as organizations if we treat public education as a public good or a private good. This issue is particularly important because the free-marketeers have argued that one key reason for adopting a privatized structure for public education is that such a structure would be so much more effective educationally than the current system (Chubb and Moe 1990).

As I have argued elsewhere, there is a growing tendency in the U.S. to look on education as a private good, whose primary purpose is to enhance the competitive social position of the degree holder, and this has brought devastating consequences for both school and society (Labaree 1997). One is that the emphasis on the private benefits of education for individual consumers leaves no one watching out for the public interest in education – no one making sure that education is providing society with the competent citizens and productive workers that the country’s political and economic life requires. Another is that this emphasis reinforces the value of tokens of educational accomplishment (grades, credits, and degrees) at the expense of substance (the acquisition of useful knowledge and skill), turning education into little more than a game of “how to succeed in school without really learning.”

Here, however, I focus on the impact all this has on the way schools work – in particular on the differences in the way that market mechanisms and political mechanisms influence the organizational effectiveness of schools. The idea is to connect the principles of publicness and privateness that define alternative visions of public schools to the organizational practices of these schools. In keeping with Tyack’s clear-eyed democratic vision of the role of public schools, I argue that the principle of public education commands our loyalty while at the same time the dysfunctional practices of public education require us to use our voices to demand reform. The peculiar blend of public and private elements within our public schools undermines their effectiveness, but the answer is not to turn them into a purely public good or purely private good. Instead we need to recognize that, even though we can exit from public schools as a private good, we cannot exit from public schools as a public good. That is, we can remove our children from urban public schools and send them to private schools or exclusive suburban public schools, but we cannot escape having to live with the social and personal consequences of the public school system we have left behind.

Exit and Voice as Responses to Organizational Decline

The best place to start in exploring these issues is with the classic book by Albert Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (1970). According to Hirschman, an organization that becomes dysfunctional – unable to satisfy the needs of its customers or members – potentially provokes two kinds of responses that offer hope of restoring the organization to a greater level of effectiveness. One is economic, in which customers exit from the organization by choosing to buy the product of another more effective firm; the offending firm either quickly gets the message and makes the necessary adjustments to bring back its customers or it goes out of business. The other is political, in which members choose not to exit but to stay and exercise their voice within the organization, in an effort to bring about the reforms they deem necessary through direct influence.

Of course, neither exit nor voice is the exclusive property of one sector or the other. Consumers often voice their concerns about bad service or faulty products to a company in the hope of correcting the problem, and voters often express their displeasure with one party by exiting and voting for the opposition. But if exit is not exclusive to markets, it is a mechanism for correcting organizational dysfunction that is natural to markets because it is so well suited to market transactions. Likewise voice is particularly well suited to political interactions. Hirschman puts it this way:

[Exit] is the sort of mechanism economics thrives on; it is neat – one either exits or one does not; it is impersonal – any face-to-face confrontation between customer and firm…is avoided and success and failure of the organization are communicated to it by a set of statistics; and it is indirect – any recovery on the part of the declining firm comes courtesy of the Invisible Hand… In all these respects, voice is just the opposite of exit. It is a far more “messy” concept because it can be graduated, all the way from faint grumbling to violent protest; it implies articulation of one’s critical options rather than a private, “secret” vote in the anonymity of the supermarket; and finally, it is direct and straightforward rather than roundabout. Voice is political action par excellence. (Hirschman 1970: 15-16)

As a political economist, Hirschman is comfortable in both arenas and sees benefits in both forms of corrective action. But he notes with some alarm that exit occupies a privileged position in American thought and practice. In part this comes from the practical advantages that exit offers over voice. All other things being equal, exit would be the preferred choice simply because it is so uncomplicated and so easy. Unlike voice, it does not require the aggrieved party to gear up for a personal confrontation with anyone in the offending organization. Nor is there a need to spend a lot of time, effort, and money in organizing a sufficient number of people to support your own position or in persuading others to change theirs. And there is every reason to expect it to produce a quick and satisfying remedy to the problem. All you need to do is drop one stock or product or candidate and pick up another. Case closed, problem solved. In contrast, the voice option brings personal stress, a costly investment of resources, and considerable risk of failure (or of success that is muted by inevitable political compromise).

In part, however, the privileged position of the exit option in American life comes from its close links to American ideology. Founded in market relations (in contrast with European countries, where markets evolved within a feudal setting), the United States has characteristically embraced notions of individual choice with more depth and warmth than most other nations, and exit has long been the preferred way to exercise this choice. After all, most American citizens are descended from immigrants, who voted with their feet by exiting the old country in favor of the new. And once here, the frontier served as a perpetual exit sign, inviting settlers to leave their current situation in the hope of finding a better opportunity elsewhere. As a result, Hirschman argues, the American character is grounded in a preference for “flight rather than fight” (p. 108), since, in the words of Louis Hartz (1955: 65 fn), “physical flight is the American substitute for the European experience of social revolution” (Hirschman 1970: 107 fn). In American terms, he notes, even success – defined as social mobility – requires you to leave the community where you grew up so you can join another that is higher on the social scale.

Exit, Voice, and the Public Schools

In this context, why should schools be any different from other American institutions? It is not be surprising to find that the exit option in recent years has come to be promoted as the preferred solution to educational problems in the United States. Reform initiatives for choice, charters, and vouchers offer educational consumers a variety of ways to leave schools they do not like and move to schools they do like. All of these reforms work by removing governmental barriers to the exercise of the exit option and increasing the responsiveness of schools to their exiting customers. The result, we are told, will be an increase in the freedom of consumer choice and a corresponding increase in the quality of education.

Of course, as Hirschman notes (along with a number of contemporary school choice advocates), some educational consumers already exercise the exit option. Parents who have sufficient financial resources frequently opt to withdraw their children from public schools that do not meet their educational standard and enroll them elsewhere. They do this either by moving to a community where the public schools are of higher quality or by staying where they are and sending their children to private schools. By their actions, these parents are treating education as a private good. That is, they are concerned about the quality of education that their children receive, and they exit one school for another in order to attain a better education for these same children. The aim of their actions, as is the aim of anyone exiting one consumer good for another, is not to improve the organization they are abandoning but to acquire the best goods for themselves. What happens to other consumers who are unable or unwilling to leave the original organization is not the concern of the exiting parties, for in a market setting every consumer and every producer is on his or her own. You make your choices in pursuit of your own self interest and you live with the consequences. The impact of your choices on others is irrelevant to your decision.

In theory, when a series of consumers choose to switch to a competitor’s product, the original producer either adapts by quickly improving quality or gets driven out of business by competitors who are already providing a quality product. This is a central tenet of neoclassical economics: the accumulated actions of consumers acting in their own self-interest result in a larger public benefit by forcing companies to lower prices and/or improve quality. But here is the catch, according to Hirschman. All too often the exit option actually serves less as a wakeup call than a safety valve for an inefficient organization, draining off its most quality-conscious and most dissatisfied customers without threatening the existence of the organization itself.

One way this happens is that organizations with similar but not identical products – McDonald’s and Burger King, Republicans and Democrats – just trade customers without either of them suffering a net loss. In education such a situation may occur between two private schools or two public schools that are somewhat different in character without one clearly being higher in quality than the other. For example, they offer different curriculum options or different kinds or degrees of religious training. But there is another way that organizations provoke the exit of quality-conscious consumers without feeling pressure to improve, and that involves situations in which there is a disjuncture between the nature of the organization and the kind of option (exit or voice) that the organization provokes when it grows ineffective.

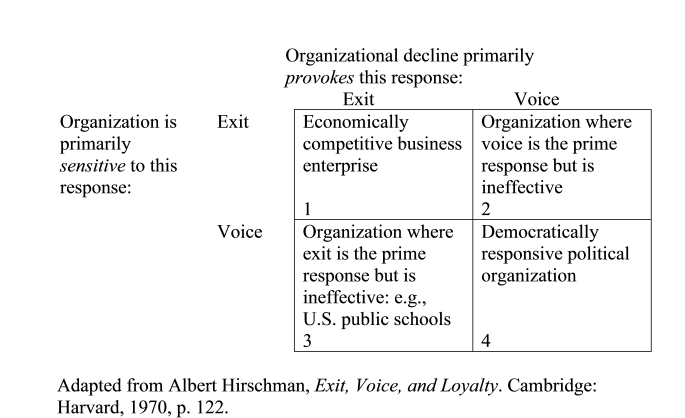

Consider the following four-fold table, which is adapted from one found Hirschman’s book (p. 122). In this table, the vertical dimension represents differences in the degree to which an organization is sensitive to exit or voice, and the horizontal dimension represents differences in the degree to which an organization provokes exit or voice in its dissatisfied customers or members. Characteristically democratic political organizations are sensitive to voice: politicians watch election results, read their mail, follow public opinion polls, and talk to their constituents in frequent trips back to the district. And ideally these same organizations tend to provoke unhappy constituents to express their voices through the same avenues that politicians track most closely. Such organizations are found in cell four on the table. Likewise, market-oriented firms characteristically are sensitive to exit: business leaders keep close watch on sales patterns and respond quickly when they see a decline or even a softness in one or another sector of the market for their products. And ideally when these same firms fall into a state of decline, they are most likely to provoke the exit response in their dissatisfied customers, who simply choose to buy a competitor’s product. These firms are found in cell one on the table. Both cell four and cell one represent efficient systems of signal and response, when organizations and their customers or constituents are in tune with each other.

The problems arise in the other two cells, when organizational laxity provokes an ineffective response. In these cases, the organization is free to continue its inefficient practices without having to pay a significant penalty. Cell two is the case of an organization that is vulnerable to exit but where exit is unlikely to occur and voice is the primary response for customers or members who wish to express dissatisfaction. One example is a company with a virtual monopoly within a particular market or market segment. Another is a political organization or voluntary association where alternatives are nonexistent or (for reasons of loyalty, identity, tradition) unthinkable. A third is any organization that turns potential leavers into stayers by making a great show of listening to and nominally responding to complaints.

Cell three is the case of an organization that is vulnerable to voice but that is most likely to provoke exit among its customers or members who become concerned about a decline in quality. Unhappily, this is the situation with public education in the U.S. As a publicly constituted, funded, and governed institution, public education is primarily sensitive to voice in resolving its problems. Consider the wide array of channels through which the public can voice dissatisfaction with public education, the numerous points of vulnerability where people can directly influence their schools: voting for school board members, school millages, and bond issues; speaking out at school board meetings, circulating petitions, and organizing protests; working through parent-teacher organizations; complaining directly to the teacher and principal; bringing to bear the influence of ethnic, religious, professional, and other voluntary organizations; lobbying the state legislature, the governor’s office, and congress; and so on. Public schools may be the most politically accessible (they are located in every neighborhood) and politically vulnerable (they are subject to myriad fiscal and popular pressures) of all American institutions.

Yet for the most quality-conscious and most politically-influential educational consumers – those in the upper middle class – the most convenient and effective mechanism for expressing dissatisfaction with public education is exit. In order to meet their educational needs, these families can afford to send their children to private schools or to move to a more affluent school district. Such a move provides a simple and immediate solution to the problem by providing their own children with the quality of education that they seek. By contrast, to stay with the original school system and pursue a remedy through the exercise of voice would be messy and time-consuming, and the results are likely to be diluted and delayed in ways that would limit the educational payoff for their children. Better to apply the market solution to the problem by switching to the better product rather than by trying to improve the old product.

This forthright employment of the exit option by upper middle class families may solve their educational problems, but it does nothing to enhance the schools they leave behind. One reason is the effectiveness of voice for provoking change in these organizations, because, as I have already noted, public schools are intensely political institutions that are primarily responsive to political pressures. Another reason is the ineffectiveness of exit for provoking change in these organizations. Why is this option ineffective in reforming schools? Because the loss of customers does not significantly threaten their fiscal base. Parents who send their children to private schools still have to pay taxes for the support of public schools, so the removal of these children reduces the costs of providing public education without reducing the income supporting this education. The case of parents who move from the city to the suburbs in order to send their children to suburban public schools is more complicated, but here too the old school district is buffered against fiscal losses. If enough wealthy families move away, property values in the old district will decline and property tax revenues for the schools will decline temporarily as well. However, two factors protect total school income from the effects of this change. One is that poor districts normally increase millage rates in order to compensate for declining property values;[ii] the other is that the state generally intervenes to subsidize district schools with markedly inadequate local resources.

The result is that the school district that is losing customers has little incentive to change its practices in order to make these customers happy. Unhappy customers are sending a classic market signal of dissatisfaction, but it is not being received because the organization is responsive only to political signals. The loss of these students actually produces a political benefit for these schools systems (as well as producing the fiscal benefit of reducing costs) , since the families who are leaving are also the ones most likely to use their voices effectively to get results. So these districts in decline manage to get rid of their most complaint-prone and quality-conscious customers without losing fiscal support. The irony, of course, is that in this case exit provokes not the taut competition and rapid corrective response that is promised by the theorists of free-market economics but instead a state of flabby complacency and continuing inefficiency. The existence of the exit option for the most financially able customers actually makes public education worse.

Promoting Exit, Creating Problems

Market-oriented educational reformers have a simple and elegant solution to this problem, one that is visually obvious when looking at Hirschman’s four-fold table: Move public education from its dysfunctional location in cell three to the functional territory of cell one. That is, make it so that public schools are vulnerable to the same corrective mechanism that they provoke among dissatisfied customers, so if they provoke exit they will also be vulnerable to exit. The result would be to transform this uncomfortable hybrid of politics and markets, of voice and exit, into a purely market institution. This is the solution that is embodied in all of the current proposals to promote educational choice, charters, and vouchers.

One key component of all these market-oriented reforms is that the funding would follow the student. The result is that if a school loses a customer, it will feel the fiscal consequences because the per-pupil funding for that customer would go with him or her to the new school. In this way, exit would get the attention of school administrators just the way declining sales get the attention of corporate managers, and they would have to adapt to these market pressures in order to win back consumers or face significant cutbacks.

The other key component of reforms pushing the cell-one option is the elimination of governmental barriers to the free exercise of school choice by educational consumers. Currently exit is possible but it is difficult and expensive. It requires the consumer to move, usually to a higher-cost community, or to stay and pay private tuition on top of public school taxes. Reform proposals call for families to be allowed to send their children to any school they want, without being restricted to the local school or even the local school district. In fact, the logic of the market-based education model would argue that consumers should also have the option of attending private secular and religious schools, and to pay for this with a voucher consisting of each child’s share of the tax monies allocated to education.

The consequences of these changes would be to transform public education into a private good like any other such good in the commodity market. Individual consumers rather than political bodies or public regulations would dictate the form and content of schooling, and they would do so simply by freely exercising the exit option. The result would be an array of schools in the educational marketplace competing for students and for the vouchers they bring with them. In the view of Chubb and Moe (1990) and others in the same tradition, this kind of market discipline, exercised by informed consumers bearing public tuition dollars, would markedly enhance the organizational effectiveness of schools in general. Public schools would have to adopt the same kinds of effective techniques and organizational mechanisms that have allowed schools in the private sector to survive and thrive under competitive market conditions.

One problem with this approach is that the putative organizational benefits of privatization are unlikely to be realized when extended to everyone. What advantages the private sector of American education enjoys over the public sector – organizational leanness and flexibility, greater agreement about educational goals, greater impact on individual students – are currently being realized in a setting where only about 10 percent of the students are attending such schools. When all students attend what in effect are private schools, these schools are unlikely to be able to realize the same leanness, flexibility, homogeneity of purpose, and educational impact that they could attain when they were a small and selective outlet for parents who are discontented with the public schools. One reason for this is that they would lose the benefit of the selection effect, since they would no longer be able to count on selecting and retaining those students who are the most able, the most motivated, and the most committed to their particular vision of education. Although proponents of the advantages of private over public education claim that they have controlled for these selection effects (Coleman and Hoffer 1987; Chubb and Moe 1990; Bryk, Lee, and Holland 1993), this claim is unconvincing in the face of the fact that only a tiny minority are currently willing and able to avail themselves of this kind of education (Gamoran 1996; Hallinan and Olneck 1982; Labaree 1997). Another reason is that it has proven notoriously difficult in education to make practices that work for the few work for the many. The history of independent progressive schools in this country provides a cautionary tale of how difficult it is to transfer reforms from a small number of model institutions to the educational system as a whole.

An even bigger problem with the market-based economic solution to the organizational problems in American education – the cell one solution – is that it is radically anti-social. By making education entirely subject to the demands of the individual consumer, it leaves no one looking out for the public interest in public education. From the market perspective, the public good is a side effect of the cumulative actions of self-interested consumers, all of whom are seeking to acquire the educational goods that are most advantageous for themselves and their families. But such a perspective assumes that members of the public have no stake in education independent of what benefits it brings to them directly as consumers of educational services – that is, as students themselves or as parents of students.

This, however, is only one way of understanding the goal of education in a modern society, one that looks on education as a private good much like any other consumer commodity whose benefits are limited to the owner. In addition, education needs to be understand as a public good. From this perspective all of the members of a community (neighborhood, town, county, state, nation) have a stake in the adequate education of other people’s children in that community in addition to their own. We all need to make sure that our fellow citizens have the skills, knowledge, and values that are required in order to function effectively as voters, jurors, and public-spirited participants in the political life of the community. And we all need to make sure that our fellow workers have the capacities and orientations that will make them economically productive in whatever occupational roles they may play, in order to promote economic growth and all the benefits that come with such growth – such as jobs, a comfortable standard of living, a broad tax base, and a secure retirement.

This public interest in education is not reducible to the sum of the private interests of all individual consumers, for in the latter situation no one is looking out for the education of other people’s children. When the school system is under pressure to provide individual consumers with a private good that will give them a competitive advantage in the race for good jobs, social status, and a comfortable life, it must adapt in ways that undermine the broader public benefits of education. Such a consumer-oriented school system must sharply stratify the educational experience in order to provide its most influential consumers with opportunities to win advantages from the system. It needs to provide educational sorting and selecting mechanisms for producing both winners and losers, for without the latter winning has no meaning. As a result we have the following familiar components of the existing highly-stratified educational system in the U.S.: ability groups in the lower grades (such as the omnipresent high, medium, and low reading groups); curriculum tracks in the upper grades (advanced placement, college prep, general, vocational, and remedial); programs for both the advantaged (gifted and talented education) and the disabled (special education); high rates of attrition at the key transition points in the system (finishing high school, entering college, finishing college, entering graduate school); and sharp differences in the social and educational benefit of graduating from high school in a rich vs. a poor district and from a college with high vs. low status.

Under these conditions, the education of other people’s children is undermined by the efforts of the most savvy and empowered consumers to get the greatest educational benefit possible for their own children. We have already seen the consequences of market pressures on American education – giving us a clear look at the nature of education in cell one – and the picture is not pretty. Treating education as a private good has not and will not provide the community with a system of education that serves the public interest. This system works well for the individual winners, but it leaves most consumers disadvantaged and it leaves the community without the full complement of competent citizens and productive workers that it requires in order to function effectively (Labaree 1997). In short, cell one is not the answer to the very real problems with the organization of education that we have been examining here.

Barring Exit, Creating More Problems

But there is another solution that is also suggested by Hirschman’s four-fold table. From this angle, the answer is to move public education from cell three to cell four, transforming it from the current muddled mix of political and market elements into a purely political institution. This would mean reconstructing education in such a way that it provoked citizens to exercise voice rather than exit when they were dissatisfied with the way schools work. By spurring the reaction to which they are most responsive, schools would become more efficient organizationally and more effective educationally. This option is attractive to those who oppose the move by the free-market reform movement to privatize public schooling, because they see public schools as a truly common ground within the community.

In Hirschman’s terms, we could accomplish this goal – shifting schools entirely into the political realm – simply by removing the possibility for an easy exit, thereby forcing people to stay and fight for improvement from within. In this view, the problem is not too little exit but too much. The existence of easy exit drains off the very voices that could change education for the better without producing any market pressures that would prompt the system to improve itself. Under these circumstances then, blocking exit altogether would provide a strong incentive for families and students to do what they can to voice their concerns in a way that will bring about positive change in the effectiveness of educational organizations.

How could this be carried out in practice? For one thing, it would require us to abolish all forms of nonpublic education, thus closing off the possibility of escape from the public sector into the private sector in education. For another, it would require us to standardize the funding of education per student across all school districts in all states, and even perhaps standardize curriculum offerings nationally as well, so that neither wealth nor geographic mobility would allow a family to exit a bad school system in order to enter a better one. If well-to-do families could no longer send their children to private schools or flee to the affluent suburbs, they would have to concentrate their efforts on improving the only educational choice available to them, their local public schools.

Such a solution has a logic to it in theory, but in practice it is unthinkably un-American. If the key problem with the market-based solution to the organizational problems in American education is that it is radically anti-social, the problem with the political solution is that it is radically illiberal. For by making education a closed public monopoly, it leaves no opportunity for individuals to make meaningful educational choices.

In her book, Democratic Education, Amy Gutmann (1987) defines the elements of a system of education that is supportive of life in a liberal democracy.

A democratic theory of education recognizes the importance of empowering citizens to make educational policy and also of constraining their choices among policies in accordance with those principles – nonrepression and nondiscrimination – that preserve the intellectual and social foundations of democratic deliberation. A society that empowers citizens to make educational policy, moderated by these two principled constraints, realizes the democratic ideal of education. (1987: 14)

To deny citizens the right to exit public schools in the manner suggested above – even if a majority of citizens supported this policy – would violate both of her core principles. It would discriminate against minority groups within society that choose to socialize their young in line with the values of that group, and it would effectively repress conceptions of education other than those expressed in the monolithic public school system.

An Answer: The Impossibility of Exiting a Public Good

Consider, however, an alternative method for moving public schools from the dysfunctional realm of cell three (where they operate without an effective feedback mechanism to correct them when they go astray) into the functional realm of cell four (where a political institution of education is responsive to the political feedback from its constituency) – without trampling all over the rights of a heterogeneous citizenry bristling with alternative visions of education. The key is to find a way to balance the public and private interests in education in such a way that the former can be met without unduly limiting the latter. Neither of the options considered so far meets this test. The all-exit market solution discounts and dismembers the public interest in education, and the no-exit political solution does the same to the private interest in this institution.

A viable way out of this dilemma is to recognize that excluding the exit option is unnecessary, since there is really no way for a citizen to escape from being a consumer of public education. As citizens, taxpayers, employers, and workers, people who send their children to private schools must still live with the consequences of public education in their community, and those who send their children to public schools in exclusive suburbs must still live with the consequences of public education in the city they left behind. They cannot avoid the social, economic, and political effects of the system of public education as it succeeds or fails in its effort to provide the political competence and human capital without which the society cannot function.

From this perspective, then, the way to convince people to voice their concerns about the failings of public education (rather than to turn their backs on these failings) is to demonstrate to them that they have an irreducible stake in the success of this institution. Since exit is functionally impossible, voice becomes the logical option, with the result that loyalty to the public schools becomes the rational choice for all citizens, whether or not they have children enrolled in these schools.

Note that I am talking about the possibility of exit from the public schools in two different sense here. Thinking of education as a private good, it remains possible for people to exit public education, and if we are going to honor Gutmann’s principles of liberal democracy, as I think we should, we cannot simply eliminate this option even if such a policy were politically feasible. As a private good, education is a form of personal property, owned by the degree holder and benefiting him or her alone. We cannot ask individuals to ignore their consumer interest in education as a private good, to act as if it did not matter whether they acquired more schooling or less, at institutions that are more prestigious or less so. Neither can we expect parents to ignore the possible advantages that education as a private good can bestow on their children. Education matters in the competition for pay, position, and life style, and no amount of commitment to the education of others can eliminate our own private interest in seeking the consumer benefits that education can grant us.

However if people are allowed to exercise choice in education in order to enhance its benefit to them as a private good, by exiting one form of education to pursue another, they still cannot exit education in its guise as a public good. This is not because they have been denied permission to leave but because “no exit” is a property of any public good. Put more positively, a person cannot be denied access to a public good, even if he or she has not contributed to the maintenance of this good. Mancur Olson puts it this way:

A common, collective, or public good is here defined as any good such that, if any person…in a group…consumes it, it cannot feasibly be withheld from the others in that group. In other words, those who do not purchase or pay for any of the public or collective good cannot be excluded or kept from sharing in the consumption of the good, as they can where noncollective goods are concerned. (Olson 1971: 14-15).

Therefore “a state is first of all an organization that provides public goods for its members, the citizens” (Olson 1971: 15). The problem for the provider of a public good, such as the state in providing public education, is that it cannot support this effort “by voluntary contributions or by selling its goods on the market” (p. 15), but must resort to compulsory means such as taxation. Otherwise there would be a large number of people enjoying a free ride at the expense of others.

There are two very important implications of this analysis for our thinking about public education. First, it is perfectly reasonable to tax everyone for the support of public schools, even those who have no children in school or those who have children in private school. In the latter case, parents are not paying double tuition for their children’s education (once in tuition to the private school, a second time in taxes for the public schools), as is frequently argued by free-marketeers. Instead they are paying one tuition for education as a private good and a second for education as a public good, whereas families with children in public schools pay only one tuition to cover both. Along the same lines, it is also reasonable to ask families in a wealthy school district to share in the support of public education for students in poorer districts (through redistributive taxation policies of the state or federal government). If we did not have compulsory support along these lines, then we would be allowing people to withdraw from the support of public education while still enjoying its collective benefits; in short, we would be allowing them to hitch a free ride on a public good.

Of course, it is one thing to say that it is reasonable to require everyone to support public education across the entire region, state, or country, even if their private interest in education is being met elsewhere, but it is another thing entirely to make this a reality. The problem, of course, is that in a democracy such mandates for the support of public institutions cannot take place without the agreement of a majority of the voters. In the case of families that are currently enjoying the benefits of education as a private good, why should they voluntarily tax themselves to support the education of other people’s children across town or in the next city? This brings us to the second implication of our analysis of education as a public good: It is reasonable for citizens to contribute voluntarily to the public education of other people’s children (that is, to agree to tax themselves for that purpose), because the indirect benefits they enjoy from this enterprise are real and compelling, and the indirect costs they would experience as a result of the failure of public education would be equally real and compelling. In short, they cannot afford to let public schools fail, even if their own children are gaining consumer benefits from education elsewhere. They cannot afford to live in a society in which large numbers of fellow citizens are unable to make intelligent decisions as voters or jurors, unable to contribute to the economic productivity as workers, and unable to follow the laws or share the values of the rest of society.

The problem with realizing this possibility, however, is that for many citizens their stake in the education of other people’s children is not at all obvious. To the extent that many Americans live out their lives at home, work, and play in groups that are made up of people very much like themselves – in race, social class, values, and social orientation – they may well feel little connection to fellow citizens who are different from them. These others may be experienced as largely invisible, unknowable, and unlikable. The social link between us and them may be very weak, and the walls that separate us from them may be felt as solid and impenetrable, with the result that we can safely ignore what kind of life they lead or what kind of education they receive. Under these circumstances, education as a public good may seem pale and peripheral compared to the robust centrality in our lives of education as a private good. Our ties to others may seem very weak and our ties to our own kind may seem very strong.

A Little Help: The Strength of Weak Ties to the Larger Community

To counter this perception, consider an interesting social anomaly – “the strength of weak ties.” The latter phrase is the title of an influential article about social networks by the sociologist Mark Granovetter (1973), in which he argues that weak ties in many ways are more important than strong ties, both to society and the individual. Strong ties are our relationships with the people who are closest to us emotionally and with whom we spend the greatest time and have the largest number of reciprocal interactions. These are our family and our closest friends. Weak ties are our relationships with people that are less intense and less involving in all the same ways. These are our acquaintances, with whom we engage in more limited and functional interactions (at work, store, clinic, etc.). Another more familiar set of terms for this distinction is primary vs. secondary relationships.

One important characteristic of strong ties is that they tend to be highly correlated; my best friends are closely aligned with the best friends of my best friends. Not only is there a lot of overlap in networks of strong ties, but the people who make up such networks tend to be similar sociologically – likely consisting of people of the same race, ethnicity, social class, cultural orientation, religion, and so on. Networks of weak ties, on the other hand, tend to be much less inward-turning. My network of weak ties is likely to have very little overlap with the networks of others with whom I have a weak tie, and it is likely to be quite heterogeneous socially and culturally.

The social consequences of these differences are striking. Strong ties pull us into a tight community of the similar and like-minded that may well be cut off from the rest of the world and that may encourage us to turn our back on those outside this group. Weak ties connect us outward to the larger community, creating avenues of access and interaction with a wide range of people and institutions that are far from our social-emotional home base within our primary group. In short, whereas strong ties support us emotionally and define us culturally, weak ties are what connect us with social life in its full complexity. Weak ties are what hold societies together in a complex web of connections and interactions, which make up in number and richness what they lack in intensity and duration. In contrast strong ties are frequently what threaten to dissolve such societies into a collection of insular and defended sub-groups based on the indissoluble link of identity rather than the fungible medium of functional interaction.

A rich network of weak ties is therefore the essential basis upon which citizens can construct a sense of public education as a public good. It is not through their strong ties to their best friends – the link of the like-minded – that they will see education as a public good but through their weak ties to acquaintances – the link of the functionally necessary. And weak ties are not only the glue that holds societies together, they are also an essential tool that helps individuals pursue their private interests within society. For example, Granovetter shows that people are most likely to find jobs not through the intervention of their best friends but through the medium of acquaintances in their network of weak ties. Why? Because that is the network that reaches out most widely into the society around the job seeker and that offers the greatest possibility of getting into a situation that is literally and figuratively farthest from the narrow world of family and friends. In these ways, weak ties are very strong and immensely useful, both for a society that has to forge cohesion out of complexity and for an individual seeking to make his or her way within that society.

Weak ties also offer us hope for our ability to establish and maintain a strong public constituency for public education, so that even satisfied consumers of education as a private good will see a reason to support education as a public good. For one thing, their inevitable network of weak ties links them to the larger society in all its variety in ways that cannot be denied or negated by their private life within the gated communities of similarity and strong ties. For another, they have every personal reason to use, extend, and reinforce their network of acquaintance and functional interaction, because it is enormously useful to them in the pursuit of their private interests. Well-educated acquaintances and potential acquaintances are essential if they want to profit and prosper in a highly-differentiated modern society. As a result, their link to the larger public that is served by public education is not so weak after all, and their stake in preserving this public arena in a state of good health and social usefulness requires of them a substantial commitment to the education of other people’s children.

Under these conditions, there is reason to be optimistic about the prospects for convincing people that they have a stake in the success of public education in its guise as a public good. Loyalty to the public schools is a rational response for citizens to adopt, even if they have chosen to send their own children to private school or to the public school across the city line. They can run from public education, but they can’t hide from its consequences. With no exit possible from this intensely public good, the only reasonable option is to speak up and pay up in order to make these schools better.

[i] For example, David Berliner and Bruce Biddle (1995) and Gerald Bracey (1997, 1996, 1995) at times have fallen into this trap. At times, so have I (Labaree, 1997).

[ii] Poor districts in the U.S. have notoriously high school millage rates while wealthy districts have notoriously low millages, since high property values in the latter districts allow them to produce higher tax revenues with lower tax rates.