This post is a piece I published in 2020 in the Chronicle Review. Here’s a link to the original. It’s about an issue that has been gnawing at me for years. How can you justify the existence of institutions of the sort I taught at for the last two decades — rich private research universities? These institutions obviously benefit their students and faculty, but what about the public as a whole? Is there a public good they serve; and if so, what is it? Answering these questions is particularly pertinent now after the recent political attacks on elite schools.

Here’s the answer I came up with. These are elite institutions to the core. Exclusivity is baked in. By admitting only a small number of elite students, they serve to promote social inequality by providing grads with an exclusive private good, a credential with high exchange value. But, in part because of this, they also produce valuable public goods — through the high quality research and the advanced graduate training that only they can provide.

Open access institutions can promote the social mobility that private research universities don’t, but they can’t provide the same degree of research and advanced training. The paradox is this: It’s in the public’s interest to preserve the elitism of these institutions.

See what you think.

HOW NOT TO DEFEND THE PRIVATE RESEARCH UNIVERSITY

DAVID F. LABAREE

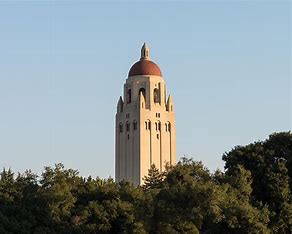

In this populist era, private research universities are easy targets that reek of privilege and entitlement. It was no surprise, then, when the White House pressured Harvard to decline $8.6 million in Covid-19-relief funds, while Stanford, Yale, and Princeton all judiciously decided not to seek such aid. With tens of billions of endowment dollars each, they hardly seemed to deserve the money.

And yet these institutions have long received outsized public subsidies. The economist Richard Vedder estimated that in 2010, Princeton got the equivalent of $50,000 per student in federal and state benefits, while its similar-size public neighbor, the College of New Jersey, got just $2,000 per student. Federal subsidies to private colleges include research grants, which go disproportionately to elite institutions, as well as student loan and scholarship funds. As recipients of such largess, how can presidents of private research universities justify their institutions to the public?

Here’s an example of how not to do so. Not long after he assumed the presidency of Stanford in 2016, Marc Tessier-Lavigne made the rounds of faculty meetings on campus in order to introduce himself and talk about future plans for the university. When he came to a Graduate School of Education meeting that I attended, he told us his top priority was to increase access. Asked how he might accomplish this, he said that one proposal he was considering was to increase the size of the entering undergraduate class by 100 to 200 students.

The problem is this: Stanford admits about 4.3 percent of the candidates who apply to join its class of 1,700. Admitting a couple hundred additional students might raise the admit rate to 5 percent. Now that’s access. The issue is that, for a private research university like Stanford, the essence of its institutional brand is its elitism. The inaccessibility is baked in.

Raj Chetty’s social mobility data for Stanford show that 66 percent of its undergrads come from the top 20 percent by income, 52 percent from the top 10 percent, 17 percent from the top 1 percent, and just 4 percent from the bottom 20 percent. Only 12 percent of Stanford grads move up by two quintiles or more — it’s hard for a university to promote social mobility when the large majority of its students starts at the top.

Compare that with the data for California State University at Los Angeles, where 12 percent of students are from the top quintile and 22 percent from the bottom quintile. Forty-seven percent of its graduates rise two or more income quintiles. Ten percent make it all the way from the bottom to the top quintile.

My point is that private research universities are elite institutions, and they shouldn’t pretend otherwise. Instead of preaching access and making a mountain out of the molehill of benefits they provide for the few poor students they enroll, they need to demonstrate how they benefit the public in other ways. This is a hard sell in our populist-minded democracy, and it requires acknowledging that the very exclusivity of these institutions serves the public good.

For starters, in making this case, we should embrace the emphasis on research production and graduate education and accept that providing instruction for undergraduates is only a small part of the overall mission. Typically these institutions have a much higher proportion of graduate students than large public universities oriented toward teaching (graduate students are 57 percent of the total at Stanford and just 8.5 percent in the California State University system).

Undergraduates may be able to get a high-quality education at private research universities, but there are plenty of other places where they could get the same or better, especially at liberal-arts colleges. Undergraduate education is not what makes these institutions distinctive. What does make them stand out are their professional schools and doctoral programs.

Private research universities are souped up versions of their public counterparts, and in combination they exert an enormous impact on American life.

As of 2017, the American Association of Universities, a club consisting of the top 65 research universities, represented just 2 percent of all four-year colleges and 12 percent of all undergrads. And yet the group accounted for over 20 percent of all U.S. graduate students; 43 percent of all research doctorates; 68 percent of all postdocs; and 38 percent of all Nobel Prize winners. In addition, its graduates occupy the centers of power, including, by 2019, 64 of the Fortune 100 CEOs; 24 governors; and 268 members of Congress.

From 2014 to 2018, AAU institutions collectively produced 2.4-million publications, and their collective scholarship received 21.4 million citations. That research has an economic impact — these same institutions have established 22 research parks and, in 2018 alone, they produced over 4,800 patents, over 5,000 technology license agreements, and over 600 start-up companies.

Put all this together and it’s clear that research universities provide society with a stunning array of benefits. Some of these benefits accrue to individual entrepreneurs and investors, but the benefits for society at a whole are extraordinary. These universities drive widespread employment, technological advances that benefit consumers worldwide, and the improvement of public health (think of all the university researchers and medical schools advancing Covid-19-research efforts right now).

Besides their higher proportion of graduate students and lower student-faculty ratio, private research universities have other major advantages over publics. One is greater institutional autonomy. Private research universities are governed by a board of laypersons who own the university, control its finances, and appoint its officers. Government can dictate how it uses the public subsidies it gets (except tax subsidies), but otherwise it is free to operate as an independent actor in the academic market. This allows these colleges to pivot quickly to take advantage of opportunities for new programs of study, research areas, and sources of funding, largely independent of political influence, though they do face a fierce academic market full of other private colleges.

A 2010 study of universities in Europe and the U.S. by Caroline Hoxby and associates shows that this mix of institutional autonomy and competition is strongly associated with higher rankings in the world hierarchy of higher education. They find that every 1-percent increase in the share of the university budget that comes from government appropriations corresponds with a decrease in international ranking of 3.2 ranks. At the same time, each 1-percent increase in the university budget from competitive grants corresponds with an increase of 6.5 ranks. They also found that universities high in autonomy and competition produced more patents.

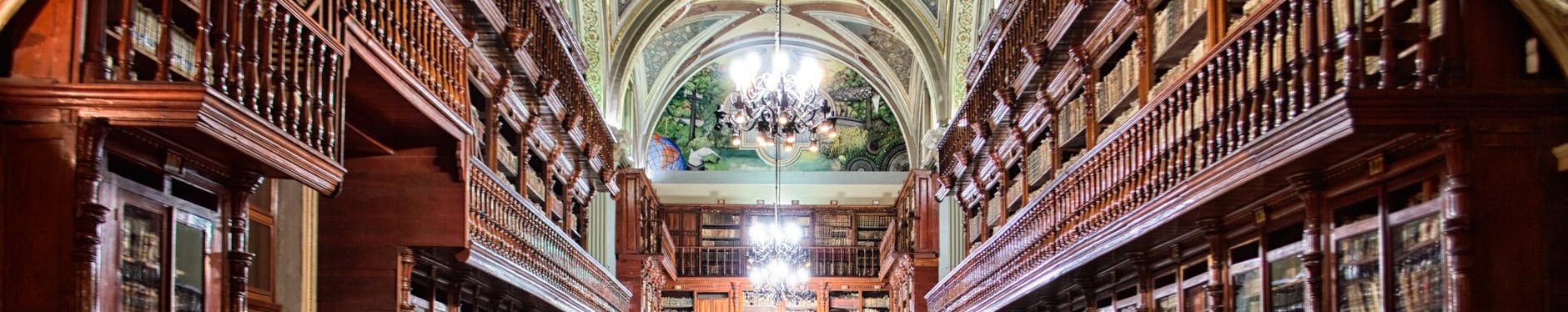

Another advantage the private research universities enjoy over their public counterparts, of course, is wealth. Stanford’s endowment is around $28 billion, and Berkeley’s is just under $5 billion, but because Stanford is so much smaller (16,000 versus 42,000 total students) this multiplies the advantage. Stanford’s endowment per student dwarfs Berkeley’s. The result is that private universities have more research resources: better labs, libraries, and physical plant; higher faculty pay (e.g., $254,000 for full professors at Stanford, compared to $200,000 at Berkeley); more funding for grad students, and more staff support.

A central asset of private research universities is their small group of academically and socially elite undergraduate students. The academic skill of these students is an important draw for faculty, but their current and future wealth is particularly important for the institution. From a democratic perspective, this wealth is a negative. The student body’s heavy skew toward the top of the income scale is a sign of how these universities are not only failing to provide much social mobility but are in fact actively engaged in preserving social advantage. We need to be honest about this issue.

But there is a major upside. Undergraduates pay their own way (as do students in professional schools); but the advanced graduate students don’t — they get free tuition plus a stipend to pay living expenses, which is subsidized, both directly and indirectly, by undergrads. The direct subsidy comes from the high sticker price undergrads pay for tuition. Part of this goes to help out upper-middle-class families who still can’t afford the tuition, but the rest goes to subsidize grad students.

The key financial benefits from undergrads come after they graduate, when the donations start rolling in. The university generously admits these students (at the expense of many of their peers), provides them with an education and a credential that jump-starts their careers and papers over their privilege, and then harvests their gratitude over a lifetime. Look around any college campus — particularly at a private research university — and you will find that almost every building, bench, and professor bears the name of a grateful donor. And nearly all of the money comes from former undergrads or professional school students, since it is they, not the doctoral students, who go on to earn the big bucks.

There is, of course, a paradox. Perhaps the gross preservation of privilege these schools traffic in serves a broader public purpose. Perhaps providing a valuable private good for the few enables the institution to provide an even more valuable public good for the many. And yet students who are denied admission to elite institutions are not being denied a college education and a chance to get ahead; they’re just being redirected. Instead of going to a private research university like Stanford or a public research university like Berkeley, many will attend a comprehensive university like San José State. Only the narrow metric of value employed at the pinnacle of the American academic meritocracy could construe this as a tragedy. San José State is a great institution, which accepts the majority of the students who apply and which sends a huge number of graduates to work in the nearby tech sector.

The economist Miguel Urquiola elaborates on this paradox in his book, Markets, Minds, and Money: Why America Leads the World in University Research (Harvard University Press, 2020), which describes how American universities came to dominate the academic world in the 20th century. The 2019 Shanghai Academic Ranking of World Universities shows that eight of the top 10 universities in the world are American, and seven of these are private.

Urquiola argues that the roots of American academe’s success can be found in its competitive marketplace. In most countries, universities are subsidiaries of the state, which controls its funding, defines its scope, and sets its policy. By contrast, American higher education has three defining characteristics: self-rule (institutions have autonomy to govern themselves); free entry (institutions can be started up by federal, state, or local governments or by individuals who acquire a corporate charter); and free scope (institutions can develop programs of research and study on their own initiative without undue governmental constraint).

The result is a radically unequal system of higher education, with extraordinary resources and capabilities concentrated in a few research universities at the top. Caroline Hoxby estimates that the most selective American research universities spend an average of $150,000 per student, 15 times as much as some poorer institutions.

As Urquiola explains, the competitive market structure puts a priority on identifying top research talent, concentrating this talent and the resources needed to support it in a small number of institutions, and motivating these researchers to ramp up their productivity. This concentration then makes it easy for major research-funding agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health, to identity the institutions that are best able to manage the research projects they want to support. And the nature of the research enterprise is such that, when markets concentrate minds and money, the social payoff is much greater than if they were dispersed more evenly.

Radical inequality in the higher-education system therefore produces outsized benefits for the public good. This, paradoxical as it may seem, is how we can truly justify the public investment in private research universities.