This post is the text of a lecture I gave in 2009 at the University of Berne. It was originally published in the Swiss journal Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Historiographie and then found its way into my 2010 book, Someone Has to Fail. Here is the link to the first published version.

It’s about a longstanding problem in American educational policy: We ask schools to pursue goals that are beyond their capabilities. Schools are simply not very good at a lot of things we ask them to do. They can’t promote equality, they can’t end poverty, they can’t create good jobs, they can’t drive economic growth, they can’t promote public health. Yet we expect them to do all this heavy lifting for us.

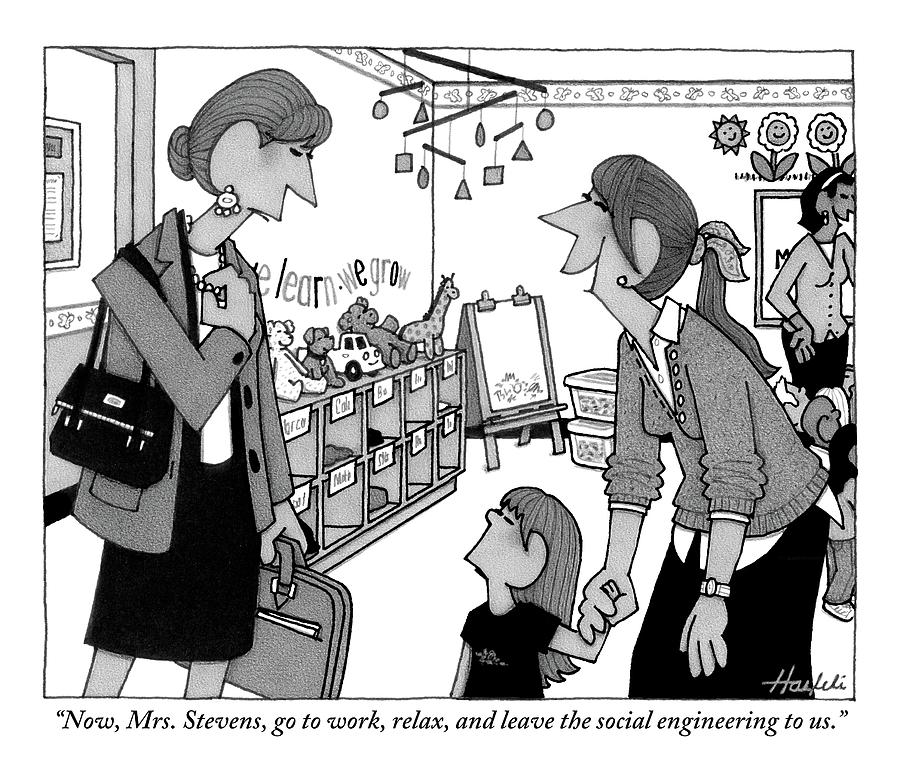

Part of the story is about why schools aren’t good at these things. Another is why we keep giving them such assignments anyway. The answer to the second, I suggest, is that we pass off on schools social problems that we are unwilling to accomplish through the political process, where the capability for success actually resides. Instead of addressing these problems directly through political action, we foist them off on schools and then blame them for continually falling short of the desired goal. Herein lies the reason why school reform has been such steady work. Read and weep.

Even if you’ve read this before, don’t miss the cartoons that I tucked into the text this time. They’re worth a post all by themselves.

WHAT SCHOOLS CAN’T DO:

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONIC FAILURE OF AMERICAN SCHOOL REFORM

DAVID F. LABAREE

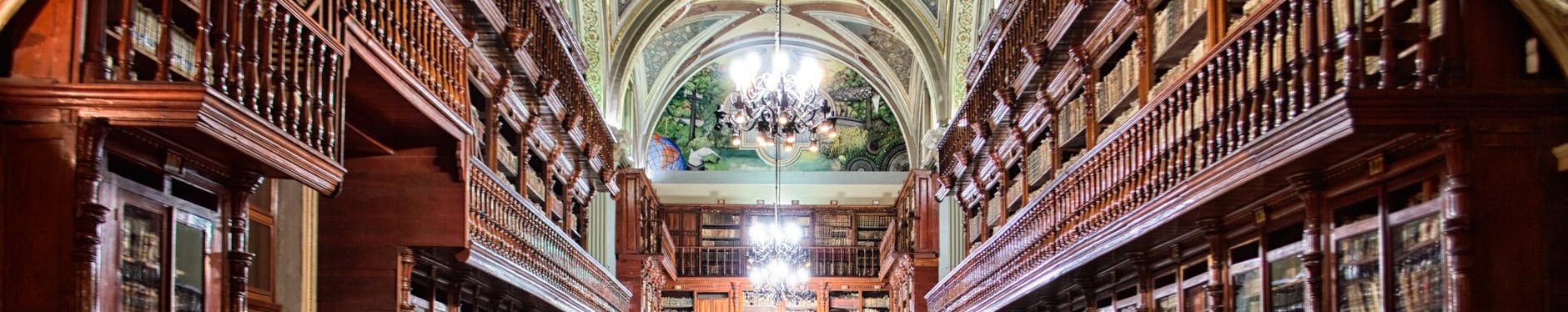

Americans have a long history of pinning their hopes on education as the way to realize compelling social ideals and solve challenging social problems. We want schools to promote civic virtue, economic productivity, and social mobility; to alleviate inequalities in race, class, and gender; to improve health, reduce crime, and protect the environment. So we assign these social missions to schools, and educators gamely accept responsibility for carrying them out. When the school system inevitably falls far short of these goals, we initiate a wave of school reform to realign the institution with its social goals and ramp up its effectiveness in attaining them. The result, as one pair of scholars has put it, is that educational reform in the U.S. is “steady work.” In this lecture, I want to tell a story: What history tells us about what schools cannot do.

At its heart, this is a story grounded in paradox. On the one hand, American schooling has been an extraordinary success. It started as a small and peripheral enterprise in the 18th century and grew into a massive institution at the center of American society in the 21st, where it draws the lion’s share of the state budget and a quarter of the lives of citizens. Central to its institutional success has been its ability to embrace and embody the social goals that have been imposed upon it. Yet, in spite of continually recurring waves of school reform, education in the U.S. has been remarkably unsuccessful at implementing these goals in the classroom practices of education and at realizing these goals in the social outcomes of education.

America, I suggest, suffers from a school syndrome. We have set our school system up for failure by asking it to fix all of our most pressing social problems, which we are unwilling to address more directly through political action rather than educational gesture. Then we blame the system when it fails. Both as a society and as individuals, we vest our greatest hopes in an institution that is manifestly unsuited to realizing them. In part the system’s failure is the result of a tension between our shifting social aims for education and the system’s own organizational momentum. We created the system to solve a critical social problem in the early days of the American republic, and its success in dealing with this problem fooled us into thinking that we could redirect the system toward new problems as time passed. But the school system has a mind of its own, and trying to change its direction is like trying to do a U-turn with a battleship.

Today I will explore the failure of school reform to realize the central social goals that have driven it over the years. And at the end I explore the roots of schooling’s failure in its role as an agent of social reform.

The social missions of schooling in liberal democracies arise from the tensions that are inherent in such societies. One of these tensions is between the demands of democratic politics and the demands of capitalist markets. A related issue is the requirement that society be able to meet its collective needs while simultaneously guaranteeing the liberty of individuals to pursue their own interests. In the American setting, these tensions have played out through the politics of education in the form of a struggle among three major social goals for the educational system. One goal is democratic equality, which sees education as a mechanism for producing capable citizens. Another is social efficiency, which sees education as a mechanism for developing productive workers. A third is social mobility, which sees education as a mechanism for individuals to reinforce or enhance their social position.

Democratic equality represents the political side of our liberal democratic values, focusing on the role of education in building a nation, forming a republican community, and providing citizens with the wide range of capabilities required to take part in democratic decision-making. The other two goals represent the market side of liberal democracy. Social efficiency captures the perspective of employers and taxpayers, who are concerned about the role of education in producing the job skills (human capital) that are required by the modern economy and that are seen as essential for economic growth and social prosperity. From this angle the issue is for education to provide for the full range of productive skills and forms of knowledge required in the complex job structure of modern capitalism. Social mobility captures the perspective of educational consumers and prospective employees, who are concerned about the role of educational credentials in signaling to the market which individuals should get the jobs with the most power, money, and prestige.

The collectivist side of liberal democracy is expressed by a combination of democratic equality and social efficiency. Both aim at having education provide broad social benefits, with both conceiving of education as a public good. Investing in the political capital of the citizenry and the human capital of the workforce benefits everyone in society, including those families who do not have children in school. In contrast, the social mobility goal represents the individualist side of liberal democracy. From this perspective, education is a private good, which benefits only the student who receives educational services and owns the resulting diplomas. Its primary function is to provide educational consumers with privileged access to higher level jobs in the competition with other prospective employees.

So let me look at how well – or rather, how poorly – American schools have done at accomplishing these three social missions.

Democratic Equality

School systems around the world have been more effective at accomplishing their political mission than either their efficiency or mobility missions. At the formative stage in the construction of a nation state, virtually anywhere in the world, education seems to have an important role to play. The key contribution in this regard is that schooling helps form a national citizenry out of a collection of local identities. One country after another developed a system of universal education at the point when it was trying to transform itself into a modern state, populated by citizens rather than subjects, with a common culture and a shared national identity. For the U.S. in the early 19th century, the key problem during this transitional period was how to establish a modern social order based on exchange relations and democratic authority out of the remnants of a traditional social order based on patriarchal relations and feudal authority. A system of public education helps to make this transition possible primarily by bringing a disparate group of youths in the community together under one roof and exposing them to a common curriculum and a common set of social experiences. The result was to instill in students social norms that allowed them to emerge as self-regulating actors in the free market while still remaining good citizens and good Christians. Creating such cultural communities is one of the few things that schools can consistently do well.

So the evidence shows that at the formative stage, school systems in the U.S. and elsewhere have been remarkably effective in promoting citizenship and forming a new social order. This is quite an accomplishment, which more than justifies the huge investment in constructing these systems. And building on this capacity for forming community, schools have continued to play an important role as the agent for incorporating newcomers. This has been particularly important in an immigrant society like the United States, where – from the Irish and Germans in the mid-19th century to the Mexicans and South Asians in the early 21st century – schools have been the central mechanism for integrating foreigners into the American experience.

But the ability of schooling to promote democratic equality in the U.S. has had little to do with learning, it has faded over time, and it has been increasingly undermined by counter tendencies toward inequality. First, note that when schools have been effective at community building, this had little to with the content of the curriculum or the nature of classroom teaching. What was important was that schools provided a common experience for all students. What they actually learned in school was irrelevant as long as they all were exposed to the same material. It could have been anything. It was the form of schooling more than its content that helped establish and preserve the American republic.

Second, the importance of schooling in forming community has declined over time. The common school system was critically important in the formative days of the American republic; but once the country’s continued existence was no longer in doubt, the role of the system grew less critical. As a result, the more recent ways in which schools have come to promote citizenship have been more formalistic than substantive. This is now embedded in classes on American history, speeches at school assemblies, pilgrim pageants around Thanksgiving, presidential portraits on classroom walls, and playing the national anthem before football games. What had been the system’s foremost rationale for existence has now retreated into the background of a system more concerned with other issues.

Third, and most important, however, the role of schools in promoting democratic equality has declined because schools have simultaneously been aggressively promoting social inequality. One of the recurring themes of my book is that every move by American schools in the direction of equality has been countered by a strong move in the opposite direction. When we created a common school system in the early 19th century, we also created a high school system to distinguish middle class students from the rest. When we expanded access to the high school at the start of the 20th century, we also created a system for tracking students within the school and opened the gates for middle class enrollment in college. When we expanded access to college in the mid-20th century, we funneled new students into the lower tiers of the system and encouraged middle class students to pursue graduate study. The American school system is at least as much about social difference as about social equality. In fact, as the system has developed, the idea of equality has become more formalistic, focused primarily on the notion of broad access to education at a certain level, while the idea of inequality has become more substantive, embodied in starkly different educational and social trajectories.

Social Efficiency

In the current politics of education, the goal of social efficiency plays a prominent role. One of the central beliefs of contemporary economics, international development, and educational policy is that education is the key to economic development as a valuable investment in human capital. Today it is hard to find a political speech, reform document, or opinion piece about education that does not include a paean to the critical role that education plays in developing human capital and spurring economic growth – and the need to reform schools in order to fix what’s wrong with the economy.

Economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz have made a strong argument for the human capital vision of education in their recent book, The Race Between Education and Technology. They argue that the extraordinary expansion of the American economy in the 20th century was to a large degree the result of an equally extraordinary expansion in educational enrollments during this period. It is no coincidence, they say, that what turned out to be the American Century economically was also the Human Capital Century for the U.S.

The numbers are indeed staggering. In the United States education levels rose dramatically for most of the 20th century. For those born between 1876 and 1951, the average number of years of schooling rose a total of 6 years, which is an increase of 0.8 years per decade. This means that the average education level of the entire U.S. population rose from less than 8 years of grade school to two years of college in only 75 years. The authors estimate that the growth in education in the U.S. accounted for between 12 and 17 percent of the growth in economic productivity across the 20th century, with the average educational contribution at 13.5 percent. Put another way, they argue that increased education alone accounted for economic growth of about one-third of one percent per year from 1915-2005.

One problem with this claim, however, is that the size of the human capital effect they show is relatively small. On average they estimate that the growth in educational attainment accounted for less that 14 percent of the growth in economic productivity over the course of the 20th century. That’s not negligible but it’s also not overwhelming. This wouldn’t be a concern if education were a modest investment drawing a modest return, because every little bit helps when it comes to economic growth. But that’s clearly not the case. Education has long been the largest single expenditure of American state and local governments, which over the course of the 20th century devoured about 30 percent of their total budgets. In 1995 this came to almost $400 billion in direct payments for elementary, secondary, and higher education. In short, as costly as education is, it would seem that its economic benefits would need to be more substantial than they are in order to justify these expenses as a solid investment in the nation’s wealth instead of a large drain on this wealth.

Another problem is that it is hard to establish that in fact education was the cause and economy the effect in this story. The authors make clear that the growth in high school and college enrollments both exceeded and preceded demand for such workers from the economy. Employers were not begging high schools to produce more graduates in order to meet the needs for greater skill in the workplace; instead they were taking advantage of a situation in which large numbers of educated workers were available, and could be hired without a large wage premium, for positions that in the past had not required this level of education. So why not hire them? And once these high school graduates were on the job, the employers may have found them useful to have around (maybe they required less training), so employers began to express a preference for high school graduates in future hiring. But just because the workforce was becoming more educated didn’t mean that the presence of educated workers was the source of increases in economic productivity. It could just as easily have been the other way around.

Producing a large increase in high school graduates was enormously expensive, especially considering that the supply of these graduates was much greater than the economic demand for them. But strong economic growth provided enough of a fiscal surplus that state and local governments were able afford to do so. In short, it makes sense to think that it was economic growth that made educational growth possible. We expanded high school because we could afford to. And we wanted to do so not because we thought it would provide social benefits by improving the economy but instead because we hoped it would provide us with personal benefits. The authors point out that the growth of high school enrollments was not the result of a reform movement. Instead, the demand for high school came from educational consumers. Middle class families saw high school and college as a way to gain an edge – or keep their already existing edge – in the competition for good jobs. And working class families saw high school as a way to provide their children with the possibility of a better life than their own. The demand came from the bottom up not the top down. Administrative progressives later capitalized on the growth of the high school by trying to harness it for their own social efficiency agenda, as expressed in the 1918 Cardinal Principles report. But by then the process of high school expansion was already well under way, with little help from them.

The major accomplishment of the American school system was not necessarily that it provided education but that it provided access. The system may or may not have been effective at teaching students the kinds of skills and knowledge that would economically useful, but it was quite effective at inviting students into the schools and keeping them there for an extended period of time. Early in their book, Goldin and Katz identify what they consider to be the primary “virtues” of the American educational system as it developed before the civil war and continued into the 20th century. In effect, these virtues of the system all revolve around its broad accessibility. They include: “public provision by small, fiscally independent districts; public funding; secular control; gender neutrality; open access; and a forgiving system.”

Note that none of these virtues of the American school system speaks to learning the curriculum. Instead all have to do with the form of the system, in particular its accessibility and flexibility. I thoroughly agree. But for the human capital argument that Goldin and Katz are trying to make, these virtues of the system pose a problem. How was the system able to provide graduates with the skills needed to spur economic growth when the system’s primary claim to fame was that it invited everyone in and then was reluctant to penalize anyone for failing to learn? In effect, the system’s greatest strength was its low academic standards. If it had screened students more carefully on the way in and graded them more scrupulously on their academic achievement, high school and college enrollments and graduation rates never would have expanded so rapidly and we would all be worse off. This brings us to the third goal of education, social mobility.

Social Mobility

In liberal democracies in general, and in the United States in particular, hope springs eternal that expanding educational opportunity will increase social mobility and social equality. This has been a prime factor in the rhetoric of the American educational reform movements for desegregation, standards, and choice. But the evidence to support that hope simply doesn’t exist. The problem is this: In the way that education interacts with social mobility and social equality, both of these measures of social position are purely relative. Both are cases of what social scientists call a zero sum game: A + B = 0. If A goes up then B must go down in order to keep the sum at zero. If one person gets ahead of someone else on the social ladder, then that other person has fallen behind. And if the social differences between two people become more equal, then the increase in social advantage for one person means the decrease in social advantage for the other. Symmetry is built into both measures.

Although social equality is inherently relative, it is possible to think of social mobility in terms of absolute rather than relative position. During the 20th century in the U.S., the proportion of agricultural, manufacturing, and other blue collar workers declined while the proportion of clerical, managerial, professional, and other white collar workers rose. At the same time the proportion of people with a grade school education declined while the proportion with more advanced education rose. So large numbers of families had the experience in which parents were blue collar and their children white collar, parents had modest education and their children had more education. In absolute terms, therefore, social mobility from blue collar to white collar work during this period was substantial, as children not only moved up in job classification compared to their parents but also gained higher pay and a higher standard of living. And this social mobility was closely related to a substantial rise in education levels. This was a great success story, and it is understandable why those involved would attribute these social gains to education. For large numbers of Americans, it seemed to confirm the adage: to get a good job, get a good education. Schooling seemed to help people move up the ladder.

At the individual level, this perception was quite correct. In the 20th century, it became the norm for employers to set minimum educational qualifications for jobs, and in general the amount of education required rose as one moved up the occupational ladder. Youths overall had a strong incentive to pursue more education in order to reap social and economic rewards. Economic studies regularly demonstrate a varying but substantial return on a family’s investment in education for their children. For example, one estimate shows that males between 1914 and 2005 earned a premium in lifetime earnings for every year of college that ranged from 8 to 14 percent. That makes education a great investment for families – better than the stock market, which had an average annual return of about 8 percent during the same period.

What is true for some individuals, however, is not necessarily true for society as a whole. As I explained about social efficiency, it is not clear that increasing the number of college graduates leads to an increase in the number of higher-level jobs for these graduates to fill. To me it seems more plausible to look at the connection between education and jobs this way: The economy creates jobs, and education is the way we allocate people to those jobs. Candidates with more education qualify for better jobs. What this means is that social mobility becomes a relative thing, which depends on the number of individuals with a particular level of education at a given time and the number of positions requiring this level of education that are available at that same time. If there are more positions than candidates at that level, all of the qualified candidates get the jobs along with some who have lower qualifications; but if there are more candidates than positions, then some qualified applicants will end up in lower level positions. So the economic value of education varies according to the job market. An increase in education without a corresponding increase in higher level jobs in the economy will reduce the value of a degree in the market for educational credentials.

This poses a problem for the chances of social mobility between parents and children. After all, children are not competing with their parents for jobs; they’re competing with peers. And like themselves, their peers have a higher level of education than their parents do. In relative terms, they only have an advantage in the competition for jobs if they have gained even more education than their peers have. Educational gains relative to peers are what matter not gains relative to parents. As a result, rates of social mobility have not increased over time as educational opportunity has increased, and societies with more expansive educational systems do not have higher mobility rates.

Raymond Boudon and others have shown that the problem is that increases in access to education affect everyone, both those who are trying to get ahead and those who are already ahead. Early in the 20th century, working class parents had a grade school education and their children poured into high schools in order to get ahead; but at the same time, middle class parents had a high school education and their children were pouring into colleges. So both groups increased education and their relative position remained the same. The new high school graduates didn’t get ahead by getting more education; they were running just to stay in place. The new college graduates didn’t necessarily get ahead either, but they did manage to stay ahead.

So school reform in the U.S. has failed to increase social mobility or reduce social inequality. In fact, without abandoning our identity as a liberal democracy, there was simply no way that educational growth could have brought about these changes. School reform can only have a chance to equalize social differences if it can reduce the gap in educational attainment between middle class students and working class students. This is politically impossible in a liberal democracy, since it would mean restricting the ability of the middle class to pursue more and better education for their children. As long as both groups gain more education in parallel, then the advantages of the one over the other will not decline. And that is exactly the situation in the American school system. It’s the compromise that has emerged from the interaction between reform and market, between social planning and consumer action: we expand opportunity and preserve advantage, both at the same time. From this perspective, the defining moment in the history of American education was the construction of the tracked comprehensive high school, which was a joint creation of consumers and reformers in the progressive era. That set the pattern for everything that followed. It’s a system that is remarkably effective at allowing both access and advantage, but it’s not one that reformers tried to create. In fact, it works against the realization of central aims of reform, since it undermines social efficiency, blocks social mobility, and limits democratic equality.

These three goals, however, have gained expression in the American educational system in at least two significant ways. First, they have maintained a highly visible presence in educational rhetoric, as the politics of education continuously pushes these goals onto the schools and the schools themselves actively express their allegiance to these same goals. Second, schools have adopted the form of these goals into their structure and process. Democratic equality has persisted in the formalism of social studies classes, school assemblies, and the display of political symbols. Social efficiency has persisted in the formalism of vocational classes, career days, and standards-based testing. Social mobility has persisted in the formalism of grades, credits, and degrees, which students accumulate as they move through the school system.

Roots of the Failure of School Reform to Resolve Social Problems

In closing, let me summarize the reasons for the continuing failure of school reform in the U.S.

The Tensions Among School Goals: One reason for the failure of reform to realize the social goals expressed in it is that these goals reflect the core tensions within a liberal democracy, which push both school and society in conflicting directions. One of those tensions is between the demands of democratic politics and the demands of capitalist markets. A related issue is the requirement that society be able to meet its collective needs while simultaneously guaranteeing the liberty of individuals to pursue their own interests. As we have seen, these tensions cannot be resolved one way or the other if we are going to remain a liberal democracy, so schools will inevitably fail at maximizing any of these goals. The result is going to be a muddled compromise rather than a clear cut victory in meeting particular expectations. The apparently dysfunctional outcomes of the educational system, therefore, are not necessarily the result of bad planning, deception, or political cynicism; they are an institutional expression of the contradictions in the liberal democratic mind.

The Tendency Toward Organizational Conservatism: There is also another layer of impediment that lies between social goals and their fulfillment via education, and that is the tension between education’s social goals and its organizational practices. Schools gain their origins from social goals, which they dutifully express in an institutional form, as happened with the construction of the common school system. This results in the development of school organization, curriculums, pedagogies, professional roles, and a complex set of occupational and organizational interests. At this more advanced stage, schools and educators are no longer simply the media for realizing social aspirations; they become major actors in the story. As such, they shape what happens in education in light of their own needs and interests, organizational patterns, and professional norms and practices. And this then becomes a major issue in educational reform. Such reforms are what happens after schooling is already in motion organizationally, when society seeks to assign new ideals to education or revive old ones that have fallen into disuse, thus initiating an effort to transform the institution toward the pursuit of different ends. But at that point society is no longer able simply to project its values onto the institution it created to express these values; instead it must negotiate an interaction with an ongoing enterprise. As a result, reform has to change both the values embedded in education and the formal structure itself, which may well resist. As I have shown elsewhere, three characteristics of the American school system – loose coupling, weak instructional control, and teacher autonomy – have made this system remarkably effective at blocking reforms from reaching the classroom.

Reformer Arrogance: Another problem that leads to the failure of school reform is simple arrogance. School reformers spin out an abstract vision of what school and society should be, and then they try to bring reality in line with the vision. But this abstract reformist grid doesn’t map comfortably onto the parochial and idiosyncratic ecology of the individual classroom. Trying to push too hard to make the classroom fit the grid may destroy the ecology of learning there; and adapting the grid enough to make it workable in the classroom may change the reform to the point that its original aims are lost. Reformers are loath to give up their aims in the service of making the reform acceptable to teachers, so they tend to plow ahead in search of ways to get around the obstacles. If they can’t make change in cooperation with teachers, then they will have to so in spite of them. They see a crying need to fix a problem through school reform, and they have developed a theory for how to do this, which looks just great on paper. Standing in the state capital or the university, they are far from the practical realities of the classroom, and they tend to be impatient with demands that they should respect the complexity of the settings in which they are trying to intervene.

The Marginality of School Reform to School Change: Finally, we need to remind ourselves that school reform has always been only a small part of the broader process of school change. Reform movements are deliberate efforts by groups of people to change schools in a direction they value and to resolve a social problem that concerns them. We measure the success of these movements by the degree to which the outcomes match the intentions of the reformers. But there’s another player in the school change game, and that’s the market. By this I mean the accumulated actions of educational consumers who are pursuing their own interests through the schooling of their children. From the colonial days, when the expressed purpose of schooling was to support the one true faith, consumers were pursuing literacy and numeracy for reasons that had nothing to do with religion and a lot to do with enhancing their ability to function in a market society.

That very personal and practical dimension of education was there from the beginning, even though no one wanted to talk about it, much less launch a reform movement in its name. And this individual dimension of schooling has only expanded its scope over the years, becoming larger in the late 19th century and then dominant in the 20th century, as increasingly educational credentials became the ticket of admission for the better jobs. The fact that public schools have long been creatures of politics – established, funded, and governed through the medium of a democratic process – means that they have been under unrelenting pressure to meet consumer demand for the kind of schooling that will help individuals move up, stay up, or at least not drop down in their position in the social order. This pressure is exerted through individual consumer actions, such as by attending school or not, going to this school not that one, enrolling in this program not some other program. It is also exerted by political actions, such as by supporting expansion of educational opportunity and preserving educational advantage in the midst of wide access.

These actions by consumers and voters have brought about significant changes in the school system, even though these changes have not been the aim of any of the consumers themselves. They have not been acting as reformers with a social cause but as individuals pursuing their own interests through education, so the changes they have produced in schooling by and large have been inadvertent. Yet these unintended effects of consumer action have often derailed or redirected the intended effects of school reformers. They created the comprehensive high school, dethroned social efficiency, pushed vocational education to the margins, and blocked the attack on de facto segregation. Educational consumers may well keep the current school standards movement from meeting its goals if they feel that standards, testing, and accountability are threatening educational access and educational advantage. They may also pose an impediment to the school choice movement, even though it is being carried out explicitly in their name. For consumers may feel more comfortable tinkering with the system they know than in taking the chance that blowing up this system might produce something that is less suited to serving their needs. In the American system of education, it seems, the consumer – not the reformer – has long been king.